The debate between intermittent fasting and frequent small meals has divided the health and fitness community for years. Both approaches claim to offer superior metabolic benefits, weight management advantages, and overall health improvements. But what does the science actually say about these two contrasting eating patterns?

Intermittent fasting has emerged as one of the most popular dietary trends of the past decade, with various protocols like the 16:8 method or 5:2 approach gaining mainstream attention. This eating pattern cycles between periods of fasting and eating windows, rather than focusing on what foods to eat. Proponents argue it taps into our evolutionary biology, as humans likely didn't have constant access to food throughout history.

On the flip side, frequent small meals - typically 5-6 meals spread evenly throughout the day - has been the conventional wisdom in nutrition circles for decades. The theory suggests this approach keeps metabolism stoked, blood sugar stable, and prevents overeating by avoiding extreme hunger. Many dietitians and trainers still swear by this method for clients seeking weight loss or athletic performance.

Digging into the research reveals some surprising findings about how these approaches affect our physiology differently. A 2020 study published in Cell Metabolism found that time-restricted eating (a form of intermittent fasting) led to significant improvements in insulin sensitivity compared to the same calories spread throughout the day. The fasting group showed better blood sugar control despite consuming identical meals.

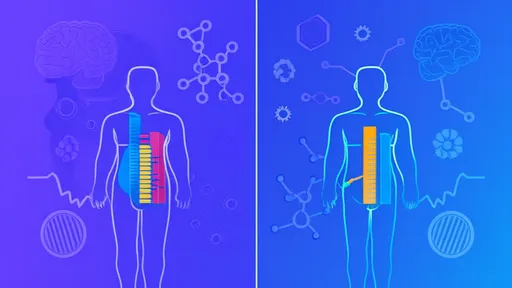

Hormonal responses tell an interesting story too. Fasting periods appear to enhance human growth hormone production - sometimes increasing levels by as much as 5-fold during extended fasts. This hormone plays crucial roles in fat metabolism and muscle preservation. Meanwhile, frequent eating keeps insulin levels consistently elevated, which some researchers believe may promote fat storage over time.

The weight loss comparison yields nuanced results. Several meta-analyses show both approaches can be effective for reducing body weight when calories are equated. However, intermittent fasting often leads to greater fat loss while preserving lean mass better than frequent small meals. This may be due to increased fat oxidation during fasting periods and the metabolic switch to ketone bodies for energy.

Digestive health presents another point of divergence. The extended breaks between meals in fasting protocols allow for what's known as the "migrating motor complex" to fully activate - waves of electrical activity that sweep the gut clean between meals. Many people report improved digestion, less bloating, and better gut motility with intermittent fasting. Frequent small meals constantly stimulate digestive processes, which may not allow for this important cleansing cycle.

Cognitive effects show fascinating differences between the approaches. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) increases during fasting periods, potentially enhancing focus, memory, and neuroplasticity. Many intermittent fasters report improved mental clarity during their fasting windows. Conversely, frequent small meals may provide more consistent fuel for those who experience energy crashes or brain fog when going too long without eating.

Practical implementation reveals why both methods persist. Intermittent fasting simplifies meal planning and often leads to spontaneous calorie reduction as people naturally eat less within compressed eating windows. However, it can be challenging for those with active lifestyles or who struggle with hunger signals. Frequent small meals offer more eating opportunities and may better suit people with blood sugar regulation issues, though it requires more planning and preparation.

Athletic performance research adds complexity to the discussion. Some studies suggest fasted training enhances fat adaptation for endurance athletes, while others show frequent meals better support high-intensity training and muscle growth. The optimal approach likely depends on the sport, training goals, and individual response.

Longevity research has produced intriguing findings regarding fasting. Animal studies consistently show calorie restriction and intermittent fasting extend lifespan, though human data remains limited. The cellular repair process of autophagy, which is upregulated during fasting, may play a key role in these anti-aging effects. Frequent small meals haven't demonstrated similar longevity benefits in research.

Psychological factors shouldn't be overlooked when comparing these approaches. Some people thrive on the structure and discipline of intermittent fasting, while others find it creates an unhealthy relationship with food. Frequent small meals may feel more natural and sustainable for those who prefer grazing throughout the day rather than having distinct meals.

Emerging research on circadian rhythms adds another layer. Our metabolism operates on a biological clock that responds to light and food cues. Time-restricted eating that aligns with natural circadian rhythms (eating mostly during daylight hours) appears to offer metabolic advantages over both random intermittent fasting schedules and frequent nighttime eating.

Individual variability plays a huge role in determining which approach works best. Genetics, lifestyle, activity levels, and personal preferences all influence whether someone will thrive with intermittent fasting or frequent small meals. What works brilliantly for one person may fail miserably for another, despite both approaches having scientific merit.

The truth is neither approach is universally superior. Current evidence suggests intermittent fasting may offer advantages for metabolic health, fat loss, and cellular repair processes, while frequent small meals may better support certain athletic pursuits and individuals with specific medical conditions. The best eating pattern is ultimately the one that an individual can maintain consistently while meeting their nutritional needs.

As research continues to evolve, we're learning that meal timing represents just one piece of the nutritional puzzle. Food quality, stress management, sleep, and physical activity all interact with our eating patterns to determine health outcomes. Rather than dogmatically adhering to one approach, many experts now recommend experimenting to find what makes your body function at its best.

Both intermittent fasting and frequent small meals can be part of a healthy lifestyle when implemented thoughtfully. The key is paying attention to your body's signals and being willing to adjust your approach as your needs change over time. After all, nutrition science continues to advance, and the most current research often emphasizes personalization over universal prescriptions.

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025