Hearing loss is often dismissed as an inevitable part of aging, something to be tolerated rather than treated. Yet, emerging research reveals a far more alarming reality: leaving hearing loss unaddressed may significantly increase the risk of dementia. Studies suggest that individuals with untreated hearing loss face up to a 40% higher likelihood of developing cognitive decline compared to those with normal hearing or those who use hearing aids. This connection between auditory health and brain function is reshaping how we understand—and must respond to—hearing impairment.

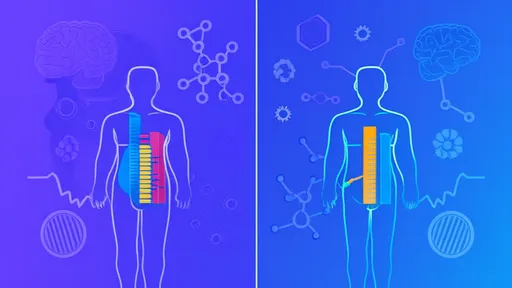

The human brain is a remarkably adaptive organ, but it thrives on stimulation. When hearing deteriorates, the brain receives fewer auditory signals, leading to a cascade of neurological changes. Researchers hypothesize that the extra cognitive effort required to decipher muffled sounds may divert resources from other critical functions, such as memory and problem-solving. Over time, this constant strain could accelerate brain atrophy, particularly in regions responsible for sound processing and speech comprehension. The resulting social isolation—a common consequence of untreated hearing loss—further compounds the risk, as reduced social engagement is itself a known contributor to cognitive decline.

One landmark study published in The Lancet followed thousands of older adults for nearly a decade. Those with moderate to severe hearing loss who did not use hearing aids were significantly more likely to develop dementia than their peers without hearing impairment. Intriguingly, the risk appeared dose-dependent: the worse the hearing loss, the higher the likelihood of cognitive deterioration. This correlation persisted even after accounting for age, education, and cardiovascular health, suggesting that hearing loss may be an independent risk factor for dementia.

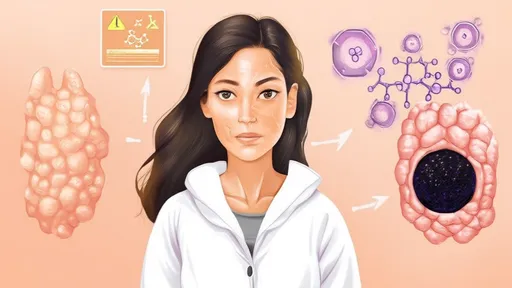

The mechanisms linking hearing loss and dementia remain under investigation, but several theories have gained traction. The cognitive load theory posits that the brain becomes overtaxed by the constant struggle to interpret incomplete sounds, leaving fewer mental resources for higher-order thinking. Another explanation centers on brain reorganization—when auditory input diminishes, the brain may repurpose sound-processing areas for other tasks, potentially disrupting neural networks crucial for memory. A third possibility involves social withdrawal; as conversations become exhausting, individuals may retreat from social interactions, depriving the brain of the stimulation it needs to stay sharp.

What makes these findings particularly urgent is the sheer prevalence of hearing loss. Globally, over 1.5 billion people live with some degree of hearing impairment, a number projected to rise with aging populations. Yet, fewer than one in five who could benefit from hearing aids actually use them. Stigma, cost, and lack of awareness all contribute to this gap. Many dismiss early signs of hearing loss—asking others to repeat themselves, turning up the television volume—as minor inconveniences rather than potential threats to long-term brain health.

Intervention studies offer a glimmer of hope. Preliminary data suggests that treating hearing loss with aids or cochlear implants may slow cognitive decline, though more research is needed to confirm the extent of this protective effect. Some experts advocate for routine hearing screenings in middle age, arguing that early detection could provide a critical window for intervention. Others emphasize the need for public health campaigns to destigmatize hearing aids and educate people about the broader implications of untreated hearing loss.

The implications extend beyond individual health. With dementia already straining healthcare systems worldwide, addressing hearing loss could represent a rare and modifiable risk factor in the fight against cognitive decline. Economists estimate that delaying dementia onset by even a few years through hearing interventions could save trillions in global care costs. Yet, realizing this potential requires a paradigm shift—from viewing hearing aids as mere convenience devices to recognizing them as vital tools for preserving brain health.

As research continues to unravel the hearing-dementia connection, one message becomes increasingly clear: hearing loss should never be ignored. Whether you're in your 40s noticing subtle changes or in your 70s struggling with conversations, seeking evaluation and treatment isn't just about hearing better today—it may be about thinking clearer tomorrow. In a world where dementia remains largely unpreventable, protecting your hearing could be one of the most actionable steps toward safeguarding your cognitive future.

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025